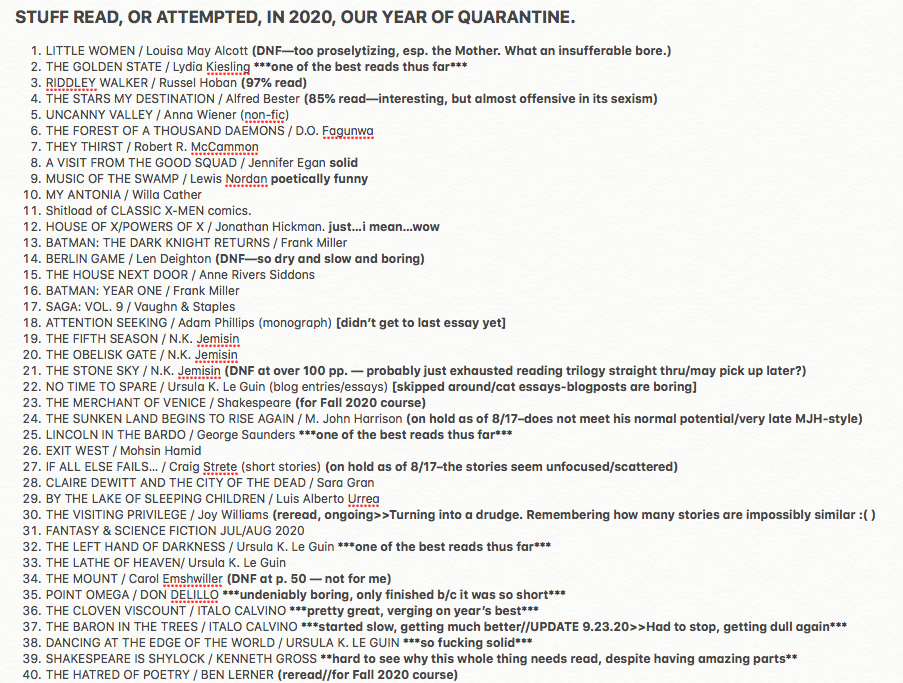

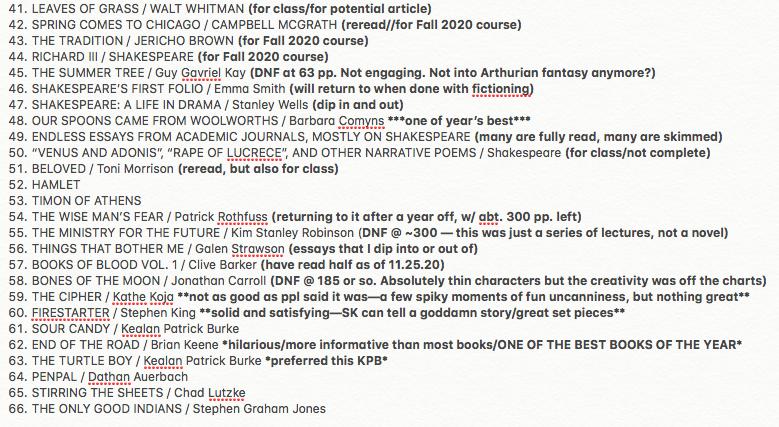

(1.8.21) STUFF READ IN 2020 AND WHAT I THOUGHT, SORT OF.

The following screenshots are from my laptop’s Notes app. Last year, before the pandemic, I started keeping track of all the stuff I read, no matter what medium. I’d never done this before, but I felt it was important to keep track for some reason. I’m glad I did. I’ll be doing this for the foreseeable future, too.

I started THE ONLY GOOD INDIANS in 2020 and finished it today (Jan. 8, 2021). It was an excellent read. I have no idea why the first screengrab has lesser resolution. Oh well.

(4.3.20) “Rm9sbG93ZXJz” X-FILES S. 11/Ep. 7.

This episode seems particularly apt for our times. And since it is impossible to write or think about anything that isn’t about the coronavirus pandemic, I figure I’d lean into it.

The episode is one of the better ones in the newest and potentially last season of this show. The title reads as inscrutable, but Wikipedia notes that it’s Base64 for “Followers.”

There is so little dialogue in this episode, it’s quite wonderful. It allows Duchovny and Anderson to play up--ham up?--their unique characters’ facial and physical tics. It is a Monster-of-the-Week type of deal, but the monster is...distributed?

Mulder and Scully are sitting alone in a sushi restaurant. The lighting is spare and spooky. No one is around. Not even staff. Our heroes are communicating through shrugs and grunts. They order food off an ipad type device. The system replies, “Yum!”, when they order and deliver the food. Scully’s order is correct. Mulder’s is horribly wrong and he gets a blobfish. Trying to find a person to take his mistake dish to, he finds a prep room in the back run totally by four Kawasaki robots which are delivering, slicing, dicing, and preparing the meals. We are to understand that this is a totally unmanned or robot-run restaurant. The bots seem bothered to have been discovered and Mulder slowly leaves.

From here it gets more nightmarish. Everything automated goes horribly wrong. Mulder’s card gets stuck in the pay slot and he doesn’t tip the robots. Scully’s self-driving cab speeds through D.C. and almost kills her. Mulder’s map app in his car takes him a roundabout way back to the sushi place.

What we easily and quickly realize is how dependent we are on AI and various tech. How it goes wrong, and constrains us. Eventually, Mulder and Scully are hounded by all of their tech. Roombas, vibrators, phones, credit card accounts, home entertainment systems, Google Home-esque systems.

All in near total pantomime.

Mulder is swarmed by drones in his own home like insects and chased out. Throughout he’s reminded on his phone that he can still tip the sushi robots. Not until Mulder and Scully are driven to a lab where they’re shot at by a 3D printer with bullets does another robot enter with Mulder’s phone, wherein he’s reminded, for the last time, that he can still tip the robots. He does, reluctantly, tip 10%. Har har.

The phone responds, “We learn from you.” Mulder says: “We should be better teachers.”

It’s both over the top goofy and eerily spot on.

We are all locked in our homes and in our devices right now. We’re on TV, phones, computers, everything is networked and connected. We are, in many ways, herded into how these devices want or need us to operate, how they were designed coerces us to act accordingly.

In an interview with Der Spiegel in 1966, Martin Heidegger said:

“I would characterize [democracy, Christianity, constitutionalism] as half truths beacuse I do not see in them a genuine confrontation with the technological world, because behind there is in my view a notion that technology is in its essence something over which man has control. In my opinion, that is not possible. Technology is in its essence something which man cannot master by himself.”

And later the interviewer asks: “And now what or who takes the place of philosophy?”

And Heidegger answers: “Cybernetics.”

Of course, for me, the question is: Who or what will help us master technology if we, humans, cannot do it for ourselves? Heidegger wouldn’t say god or spirit or anything like that. So what then?

The episode ends with Mulder compromising and giving a little of what the robots want. There is a tenuous understanding between technology and humanity. I wonder if that’s the future of this relationship?

I do not want to be like a robot and do not want a robot to be like me.

(2.28.20) Commonplace Book; Anna Wiener’s UNCANNY VALLEY.

I want to (plan to) review this book, but also want to just toss up here a bunch of sections of Wiener’s memoir that I thought were plainly great. There’s a wonderful essay, influential to me, by the critic/poet Randall Jarrell called “Some Lines from Whitman.” Jarrell’s argument is that Whitman is such a great poet, and at the time, misunderstood, that merely quoting select lines of his should be enough to win over the undecided. Jarrell does interpolate quite a bit, tho. Rightly so. And he shows why the lines are so good. I feel the same way about Wiener’s observation in UNCANNY VALLEY. The following entries are representative of the metier of the book. I will refrain from interpolating just yet, tho.

p. 41: Noah was warm and loquacious, animated, handsome. He struck me as the kind of perosn who would invite women over to get stoned and look at art books and listen to Brian Eno, and then actually spend the night doing that. I had gone to college with men like this: men who would comfortably sit on the floor with their backs against the bed, men who self-identified as feminists and would never make the first move. I could immediately picture him making seitan stir-fry, suggesting a hike in the rain. Showing up in an emergency and thinking he knew exactly what to do. Noah spoke in absolutes and in the language of psychoanalysis, offering definitive narratives for everyone, everything. I had the uneasy feeling that he could persuade me to do anything: bike across America; join a cult.

p. 59: As we walked back to the office, I told him about my friends in New York, and how they didn’t seem to understand the appeal of working in technology. In the elevator, we joked about building an app that might interest them, one that would algorithmically suggest pairings of cocktail recipes and literature, according to a given book’s mood, era, and themes. I returned to my desk and didn’t think about it again--until the following afternoon, when the CTO messaged me in the company chat room and told me he had built it.

p. 68: Does that make sense? I’d ask every few minutes, as gently as a tutor, giving them space to shift the blame back to me.

p. 69: Some days, helping men solve problems they had created for themselves, I felt like a piece of software myself, a bot: instead of being an artificial intelligence, I was an intelligent artifice, an empathetic text snippet or a warm voice, giving instructions, listening comfortingly.

p. 93: Sometimes it felt like everyone was speaking a different language--or the same language with radically different rules. There was no common lexicon. Instead, people used a sort of nonlanguage, which was neither beautiful nor especially efficient: a mash-up of business-speak with athletic and wartime metaphors, inflated with self-importance. Calls to action; front lines and trenches; blitzscaling. Companies didn’t fail, they died. We didn’t complete, we went to war.

“We are making products,” the CEO said, building us up at a Tuesday team meeting, “that can push the fold of mankind.”

p. 113: Being the only woman on a nontechnical team, providing customer support to software developers, was like immersion therapy for internalized misogyny. I liked men--I had a brother. I had a boyfriend. But men were everywhere: the customers, my teammates, my boss, his boss. I was always fixing things for them, tiptoeing around their vanities, cheering them up. Affirming, dodging, confiding, collaborating. Advocating for their career advancement; ordering them pizza. My job had placed me, a self-identified feminist, in a position of ceaseless, professionalized deference to the male ego.

p. 167: Self-improvement appealed to me, too. I could stand to exercise more often, and be more mindful of salt. I wanted to be more open and thoughtful, more attentive and available to family, friends, Ian. I wanted to stop hiding discomfort, sadness, and anger behind humor. I wanted a therapist to laugh at my jokes and tell me I was well-adjusted. I wanted to better understand my own desires, what I wanted; to find a purpose. But nonmedical monitoring of heart rate variability, sleep latency, glucose levels, ketones--none of this was self-knowledge. It was just metadata.

(2.24.20) Inevitability Machines.

I write short stories at a pace generously labeled “slow.” I wonder about this a lot. It’s a newer development in my writing. I used to start and develop plenty of ideas and drafts of stories. But lately, stories reach an interminable deadlock on the first few pages.

And I think I’ve finally realized why.

For me, stories run on a different logic than novels. I’ve been working on longer projects in the past few years, and so it makes sense to see stories as strange foreign diadems, impossible to manufacture with my current gears and pulleys.

If a story does arrive it’s usually in a full lump, written quickly. I wonder about that...

But anyway, the logic. I can see all of the story. And its flaws and strengths and peaks and dips are all available in one long widescreen vision. It’s maddening to have all that information looking at you. And it’s like a puzzle. Every story.

I was writing to a friend how much I dislike story endings that are clean-cut. Occasionally, a story with a strong definitive ending is called for, but often I’m on board with unraveled and smudgy endings that make a reader second guess what they read. I prefer stories that produce and encourage moods rather than conclusions; withholding rather than freedom; implication over explication; doubt over certainty, etc. All of which is frustrating as hell.

I’ve been thinking of stories now as Inevitability Machines. What do I mean by this?

What I mean is: if anything, the ending of the story is a drain that pulls everything toward it in this feeling of inevitable force, like a black hole’s event horizon. This only can be realized retrospectively, tho. When reading the story for the first time, anything can happen. But at the very end, the last line, I want myself and the readers to turn over their shoulder and see how none of it could’ve been changed. That this was how it was to be from forever, from day dot.

There’s this darkly humorous story by Mark Richard called, “Strays,” in his bone-sharp and Southern Gothic collection, THE ICE AT THE BOTTOM OF THE WORLD. “Strays” is circular. Inevitable. The story is first person, told by a young boy, an older brother. He describes how he and his younger brother are left alone after his mother runs away and leaves the father with them. The father goes after her. Thus, they are to fend for themselves. Stray dogs show up at the house and the boys name them, try to play with them, etc. Innocence and tragedy ensue. A ne’er-do-well uncle shows up to “babysit.” The uncle has a refrain everytime he leaves the boys alone, again, “Don’t y’all burn down the house.” Naturally, the house burns down. At the end, the father finally brings the mother back, but not before he decks the uncle. In the melee, the mother takes off again, repreating, almost verbatim, the opening lines.

The story is inevitable, and tho I know I just said it was circular, now I’m thinking it’s more spiral. Because the story doesn’t end where it began. It ends further than where it began. But the reader, this reader, always feels like there was no other way for the story to turn out. It has to, must, end in the fashion it does. You may ask, “Don’t all stories do this?” Well, no. Many don’t. Often, they don’t. I think most stories end, and the reader can imagine or feel or desire an alternate ending. A variant.

I don’t have a methodology. It’s a know-it-when-I-see-it kinda thing. Which I hate and love. Let me know if you have suggestions on this. How to do it, recreate it, etc.

(1.10.20) It’s Not a Trope; It’s a Topos.

For two years, I submitted myself to torture by a group of likeminded and intelligent adults. They went by the moniker of a “Dissertation Committee.”

The torture was, of course, metaphorical. But working on a dissertation while also working at a medical tech start-up and having a new baby and revising a novel was like wearing crazypants in Psychotown. One of the few enjoyable aspects of writing a dissertation on English, rhetoric, and writing was that I got to discuss and think through a concept called “troping.”

Basically, troping is when a writer (in my case, a college student writer) takes a linguistic pattern from a previous tradition or particular writer and changes or warps it—that is, tropes on it. In Greek, tropos means “to turn away” and so it makes sense to see how a college student, working hard to define themselves in opposition to everything else they’ve seen or heard, and in a move to delineate a spot for themselves in the writing world, will, and do, take what exists and turn it a bit. Everyone does it. I just wanted to study that process in detail and see what came of it. Good times.

Well, sort of.

I noticed, as I began to submit stories to more and more science fiction and fantasy magazines, and to engage and read more in that community, that in the SFF world there is a tendency to talk about tropes and how they are either old, tired, stale, or—on the other hand—how they are being revived or renewed or given new blood, etc.

It always rankled me a bit, because I knew that what most people meant when they said that “There’s a trope in this story that is cliche” or “That book relies on old tropes” was something like, “There’s a topos in this story that is cliche” or “That book relies on old topoi.”

It’s not a trope; it’s a topos.

Whereas a trope/tropos is a turning away or a change, a topic/topos is a place or an area, so to speak, where writers retrieve ideas. Tropes are mobile and topics are static, metaphorically speaking. So when you read a zombie story, you’re likely waiting for the place in the story where you learn about how the infected became zombies. Virus? Alien meteor? Ancient demonic curse? Spoiled meat bacteria? Hi-jacked computer code? You’ll also wonder—are the zombies fast or slow? Are they smart or dumb? Are they weak or strong? Etc. Each of these is a place, a topos, to go and retrieve an idea and bring it back to the story. If the topoi is used too often, if, that is, we visit the locus communis too often, they can become hackneyed ideas, commonplaces, cliches. Everytime you watch a detective show and the lead character is an alcoholic or has an irrepressible urge for self-destruction, then we’re dealing with a commonplace, an overused topos.

However, if that detective show sees the main character obsessively making brownies for their clients and bouncing ideas off of a stuffed rabbit that they won at a carnival as a 12 yr old, then, perhaps, the writer has troped the topos. They have changed or “turned away” from the commonplace and, as they say, made it new or newish.

I googled this to see if anyone else has noticed this, and there was this article from a few years ago in The Spectator, “Why it’s time to abandon ‘trope’”. Everything I said here was mentioned there by Dot Wordsworth, give or take some historical points. So, some folks are pointing it out. But, to no great effect, I think. I’m, for the most part, a descriptivist with prescriptivist tendencies, where I think the history and etymology of a word better serves the present over the whims and fashions of the present. Also, a word’s meaning can, and often is, agglutinative or accretive—one piece piles onto another to help shape how all those individual pieces mean and work.

Why change “trope” to mean something it’s not when we have a perfectly good word already in use—topos? Probably because TV Tropes sounds better than TV Topos.

(12.21.19) Idle (and Inevitably Reductive) Commentary on What I’ve Learned about Writing Horror from Reading Horror.

- It’s not about scaring people, which, I think, is quite difficult to do. At least in prose. When reading fiction that is self-identified as “horror,” I’m always surprised by how not terrifying it is. It often seems like writing taken out of context has more of a scary feel to it. That is, writing not meant to induce unease is the best at inducing unease. A screenshot of a text back and forth. A handwritten letter found on a sidewalk clearly written by a child but in a voice that’s waaay too mature for a child. And so on. I think writing horror is about putting people in a state of confusion that they can’t immediately correct or escape from. Perhaps can never escape from.

- This might mean that a lot of what you’re reading/watching is horror even though it’s never self-identified as horror or is aware of the horror conventions. (I am happy to be wrong about this or seen as misguided.) But let me proceed to see where this goes...

- As many horror writers already know (and I’m not necessarily saying that’s what I am) is that horror is more often about--or gets much of its effects/affects from--anxiety or suspense. [Q.v. the bold claim above.]

- Which leads me to this tension & release theory. Some of the best horror I’ve read does two thing really well: (a) it puts you into an uneasy relationship with the characters/setting that is productively confusing or eliciting a need to know. That’s the tension. The release is when the reader is made aware or given a potential answer to the reason why the tension existed. And (b) it plays with “peripherality.”

- What do I mean by “peripherality”? This is side-of-the-eye stuff. Imagery, words, tropes, characters, events, whatever, that occur just far enough out of the eyeline of the reader that they spark/elicit attention. But then that will become an irritant. A piece of sand under the eyelid, so to speak. A piece of foil in your food. You begin to mess with it, play with it, think on it, question it. And the more you ask of it, the deeper it goes. That’s peripherality to me.

One of the best examples I can think of here is Roberto Bolaño’s 2666. I consider this whole novel a horror novel. Many of his best ones are, I think. Distant Star. By Night in Chile. Anyway. The book is split into five sections, and in the second section (”The Part About Amalfitano”) there is mention of a car, a black muscle car, in connection with an on-going string of murders of young women. The car prowls the streets of the Mexican city of Santa Teresa. But it’s not made an explicit part of the dialogue. It’s mentioned here and there. Only in passing. But it’s these passing moments that build into a swirl, then a storm. By the end, even the mention of any black car creates dread in the reader. Bolaño puts the car and a character, Rosa, into juxtaposition with one another and lets us create the anxiety between them. He doesn’t have to actually put them into a direct relationship. That, to me, is the essence of horror. And it creates anxiety better than much strictly-labeled and promoted horror fiction.

The fourth section (”The Part About the Crimes”) does this, too. The peripherality here is the constant repetition of a body part, the hyoid bone, which is often crushed when a person is strangled. Endless bodies of young women are discovered in vacant lots in Santa Teresa with broken hyoid bones. The dread mounts when you hear the word because you know that it’s connected with all the others. But Bolaño never has to explicitly say this or lay this out. He just sets it in a conjunctive relationship with the characters who are exploring the murders. Would you be surprised if I said that the black muscle car makes an appearance and collapses hundreds of pages to induce a deeper unease than I have known anywhere prior?

Some Examples:

The “main/most talked about” character in 2666, Arcimboldi, is pure peripherality. (Until he shows up.)

Barlow in ‘Salem’s Lot is pure peripherality. (Until he, too, shows up.)

In Hereditary, the dead grandmother.

David Fincher’s Zodiac is 100% peripherality. This makes sense, though, because so much of the movie is about procedure and research, which, by definition, is peripheral to the murders. Even in the violent scenes where murders occur, the killer is seen peripherally and, in the most graphic scene at Lake Berryessa, the camera is set as if we’re seeing it from the peripheral view.

I think a lot of Joy Williams’s stories/novels have horror elements like this. E.g. “Marabou,” The Quick and the Dead, the story she wrote about Jared Loughner.

Dan Chaon’s Await Your Reply is, I think, a study in peripherality. The whole time I read the book I kept thinking, “A Lovecraftian creature could appear, there could be a cult, this could all turn out to be a haunting, or schizophrenia, or another dimension colliding with ours.” It takes patience not to give a reader an out-and-out motivation or rationale. And it works.

(12.14.19) The Emily Dickinson Speculative Fiction Machine.

This is an exercise wherein I chose a line from a random ED poem (the # in bold is taken from the Franklin reading edition) and try to write a few lines of a possible story around it. I may post a few more here and there.

1695. “No mirror could Illumine thee like that impassive stone,” Hneida said.

Farleigh swallowed the plain and unassuming rock. He had to fight the urge to chew it. Once it passed his gullet, he began retching and choking. Hneida grabbed him from behind and shut up his jaw with one hand and stayed his bucking torso with the other. Her strength worried him more than the choking.

Finally, the rock passed through. He felt it drop heavily into his stomach. It felt as if the only thing inside of him were the rock and all else was absorbed into it. As if he was some kind of delicate pastry with a sweet filling.

He said this to Hneida.

“That’s because you are a shell. The rock did absorb all of you.”

“For an alchemist you are rather dispiriting. You have zero bedside manner.” Farleigh kneeled to gather himself. “Now what?”

“Now when the rock deems its work done, you’ll puke it up. Then we’ll take it to a corn field that’s been left to seed for at least three years, and bury it in the exact middle. Then we hope for rain within the week.”

“And if not?”

“Then we have to do this all over again.”

“And when it rains then I’ll have my double?”

“Yes, your double will come from the barren ground and will live, mostly, in the rock. Like I said, it’s better than a mirror. It’ll Illumine you with more precision. In a sense, it’ll be more you than you will.”

That wasn’t a problem for Farleigh. He needed something more human than human since he didn’t plan on being human that much longer anyway.

His stomach roiled and he clutched his belly button.

“Oh, stand back,” he said.

But the alchemist had already given her patient a wide berth.