Recently Read & Reviewed Archive

[12.31.19]

The Cabin at the End of the World by Paul Tremblay

For three months in the summer of 2009 I lived in the middle of nowhere Indiana. West Central Indiana, to be precise. I didn’t live in a cabin, but I lived in a 1950 Peerless trailer. Fifty feet long, knotty wood panelling, asbestos kitchen tiles. It was both glorious and a death trap. The windows leaked, it had no heat, no AC, and it was hooked up to well-water, so after every shower I smelled like a bag of iron filings. I lived on homemade Italian wedding soup and almonds, read Dickens, talked at-length to my cat, and at night--sat on my concrete patio watching the sunset and swatting mosquitoes. I also kept a huge bucher’s knife under the pillow next to me.

It was, in some sense, idyllic. The lake, not the knife. And that’s what Paul Tremblay wants to set up in the beginning of The Cabin at the End of the World: a sense of the idyl destroyed. A couple, Andrew and Eric, with their adopted Chinese daughter, Wen (7 y.o.), are spending time in rural Vermont in a lake cabin that is two miles from any form of civilization. As Wen is collecting grasshoppers in the lane leading to the cabin, a massive man named Leonard appears and makes friends with her, & then, in classic horror novel fashion, unspools a wack-tastic speech about having to make hard choices and needing help to save the world. Three other strangers walk out of of the woods holding Mad Max: Fury Road-esque weapons/instrumentation. Immediately, on the face of it, Cabin stares you in the face and says, “Here is your pre-fabricated home invasion story. Try to anticipate me.” Reader, you cannot. Because the book takes all the tropes of home invasion and shoves them into a bloody Cuisinart and mashes down the ON button with a pirate hook and gargles baby tears.

Normally, the invaders would work to break in, and once in, chase down, hurt, mangle, murder, and desecrate the homeowners. But things are different here. Other than forcing their way in with gentle suggestions and some physical force, the invasion is underwhelming (a good thing!). I kept thinking, what’s the real motivation here. When does the shoe drop? [Should also mention here that the book does a weird move wherein it’s split into different parts/sections for reasons that weren’t clear to me--the whole book into three parts and the chapters are split between “different” POVs. These weren’t proper, clear different POVs. Just that the emphasis was shifted differently, it seemed. Except for one or two sections near the end that mess with a collective first person, the whole book is a roaming close-third told in the present tense.]

The shoe drops when Leonard & Co. (Redmond, Sabrina, Adriane) tie up the family (except Wen) and declare that the three of them will have to choose one of their own to sacrifice or the world will end in an undetermined amount of time. Okay. So. I begin to wonder, why are the other three folks there? Ahh. They are there because as time goes by, if no decision is willingly made, they murder one of the invaders as a way to urge Andrew and Eric and Wen to choose. There is a back and forth here--the bulk of the book--where the narrative pretty much asks this question: “Is Leonard and his dream visions about the end of the world and the need for a sacrifice by Andrew, Eric, and Wen real or fake?” In this regard, the book reminded me very much of the amazing Jeff Nichols 2011 film Take Shelter. Viz., Is the normal person going crazy actually crazy or cognitively aware of some unforeseen danger?

Tremblay sets up everything that may point to an answer with such subtlety that you never really find out if the world may end or no, depending on what actions the family takes. But it’s always pushing you in one direction or another. I can imagine that Tremblay had a great time messing with the reader while writing it. For example, each time an invader kills one of their own, they’re supposed to check the national TV news and see what the chyron holds. Plagues, tsunamis, mass airplane crashes? Each one of these is presented in such a way as to be either prescient or pure coincidence. To make matters truly worse--the part that really turned up tension for me--was the on-going debate between the husbands, Andrew and Eric. Andrew is clearly the pragmatic, empirical one. No nonsense atheist. Eric has a religious background (Catholic) and is open to non-terrestrial explanations. And especially after a violent concussion near the beginning of the invasion, he, too, is sometimes siding with the invaders.

The horrific part of this book has two real pieces. One of which I will not divulge here. But the other is what I just mentioned. The feeling of slowly and inevitably losing contact and trust with your significant other. The feeling--and dreadful realization--that you may not have known someone as well as you thought you did, the one person you trusted and gave everything to. There is also a frustrating sense of how inadequate the art of rhetoric is here in this book. As someone who studies and teaches persuasion, rhetoric, writing, argument, I’d like to think that rhetoric can be a powerful tool. But, in reality, I always come down recognizing that bia, or force, will win out over peitho, or persuasion, in most contests.

That’s probably why I kept the knife under the pillow. Evil is tough to negotiate with when it sees the steel in your hand.

tl;dr

Yummers: See my comments on peripherality in horror on the main page--Tremblay is so good on this. Much like Dan Chaon. You never know what the truth is. Some horror novels are horrific because you see a monster or an devil climbs into a person’s armpit and takes control of their bowels. But here, Tremblay writes a suspense story on the teeth of a chainsaw and spends the whole time flexing his hand and popping his knuckles before pulling the ignition rope.

Also: that true horror is the clash of irresolvable ideologies--empirical vs. superstitious, etc.

Bummers: There was a move in this book--deployed many times--wherein Tremblay would pause in the middle of action to take a longish emotional look at a character’s past. While not bad or clumsy or anything like that, it did significantly slow down the pace of the book. And many times, I felt like I didn’t need that specific backfill for my Motivation Button to be pushed. In horror, it seems that authors have a hell of a time trying to balance the sheer thrill of the genre’s content with trying to round out the characters are more than meat packages to be sliced open and fed to the hellhounds. Tremblay gets credit here for trying, but I’m not sure all of it was necessary. As a writer who does this, perhaps I’m just biased and feeling guilty about how transparent some of the moves of fiction writing can be.

Also, some of the deaths in this book were handled with a little underwhelmingly when I would imagine that the deaths would cause much more soaring grief and unhinged violence.

[12.19.19]

My Best Friend’s Exorcism by Grady Hendrix

Once, in middle school, I got a perm. A loose one, not a Greg Brady-type thing. It’s not something I look back on fondly, but I sort of wear the fact like a fucked-up badge of honor. The Redken Badge of Courage, you might say. (”Booooo!”) Anyway, like all pre-mass shooting schools in the Midwest, before classes started, students amassed in the gymnasium. Each grade sat separate. Cool kids with cool kids. Dorks with dorks. Athletes with athletes, etc. etc. As I sat one morning, a person, who’s name I remember, but will not divulge here, caught sight of me with my loose, gelled, permed hair and made a jacking-off motion. He caught the invisible jizz in his hand and ran it through his hair, mimicking what I could only guess he thought was my daily routine. His squad of typical seventh/eighth graders jumped on the gag and took 15 seconds out of their day to humiliate me. I relay this anecdote because it only sharpens my appreciation of My Best Friend’s Exorcism, which, if anything, most excellently portrays (like some kind of fucking cinema verite) the absolute grunge horror of being 12, 13, 14 years old with other morbidly tragic people trapped in sweaty, morphing, hormone-jolted fuckboxes. I hated my past experience with the hair jizz gel, but I’m glad it was there to better appreciate the scope of Hendrix’s book.

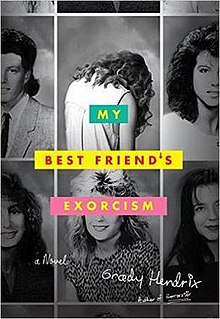

I found Grady Hendrix’s fiction through his non-fiction work about the 1980s horror fiction boom--Paperbacks from Hell. I’ve sunk myself into horror/thriller/suspense as of late, and I wanted to see what Hendrix’s own work was all about. And, to be honest, the cover of My Best Friend’s Exorcism is what doubly sold me. I mean, look at that! The art direction at Quirk Books is always solid and thorough (note that the apostrophe in the word “friend’s” is an upsidedown cross). The 80s color scheme (much like this website’s) and the handwritten work at the bottom mimicking the yearbook. Of course, the spot on class photos with teased bangs and animal print tops. What you can’t see from the pic is the interior flyleafs which look like the front and back of a high school yearbook, complete with original handwritten comments to the main character, Abby. There’s also a few pages of local Charleston, SC ads. Every chapter title is named after a pop single from the 80s. If you’ve got a jones for all things Reagan Era, this book will satisfy your craving.

But then we get to One of These Things Just Doesn’t Belong...When I saw the girl turned away from the camera, the imagination goes into overload as to what she could look like on the other side. It terrifies. I’m still captivated by it.

And it’s nice when the packaging assists the content in its goal. MBFE in itself is creepy, spooky, and tense. I definitely kept turning the page to see what would happen next. I say that up front because it’s selling itself as a horror novel, and often when I read horror, I’m rarely moved. (E.g. Nick Cutter’s The Troop, while gross, was not tense or scary or horrific. In fact, one could argue that Hendrix takes the premise of Cutter’s book and makes it a whole lot more effective in two or three pages toward the end of the book--but that’s a spoiler, sort of.)

So, the plot. Abby and Gretchen are besties starting around 1982 with the release and hoopla around the movie E.T. In Charleston, SC, Abby has a birthday party at a rollerdome and no one shows except Gretchen, who has given her a Bible as a gift. That’s horrific. Abby is distraught--but Gretchen shows herself to be loyal. These two grow up to attend a private high school, Albemarle, and share everything despite coming from opposite economic backgrounds. Abby’s parents are lower-working class. Gretchen’s are upper-class genteel Christian gas-bags. Hendrix has fun with stereotypes here, but gives even the dickheads some soul. E.g. even though Gretchen’s parents eat farts, they are open to taking Abby with them everywhere: vacations, dinners, sleepovers, whatever. As a lower class kid who made friends with monied kids--this kinda shit rang too true.

As sophomores, one night Abby and Gretchen, along with two other richy chicks, Margaret and Glee, decide to drop some acid.

“You guys want to freak the fuck out?” Margaret Middleton asked. (41)

The acid doesn’t take. Instead Gretchen decides to go skinny-dipping. She leaps off a pier into a low tide and disappears. The girls spends hours looking for her. Into the dawn, Abby eventually comes across an old historic building in the woods where odd stirrings emerge. And then Gretchen does. Confused, bloodied. Abby thinks her best friend has been raped by a local low-life. Especially when Gretchen begins acting strange. She goes from gorgeous, put-together, star student to brittle, stinky, falling-apart loser. Gretchen doesn’t want to talk about it and Abby doesn’t know how to fix it. In high school, close friendships are everything. And this one is on its deathbed. Gretchen barfs weird white stuff, she feels hands on her neck all the time, and a flock of birds fly into her living room windows, killing themselves. Gretchen descends into hell.

Abby couldn’t entirely blame them. It was getting harder and harder to be seen with Gretchen. At first she’s just recycled the same calf-length gray skirt that she wore too often anyways because some senior once said it made her look hot. Then Abby noticed that Gretchen wasn’t wearing makeup anymore. Her nails were always dirty and she was chewing them again.

Plus, she was starting to smell. This was no simple whiff of bad breath; it was a constant sour stink, like the boys after PE. Every morning Abby wanted to crack her window, but they had a rule: the Bunny’s windows stayed up on school days. Otherwise, she’d have to respray her hair when they got to Albemarle.

“Did you step in something?” Abby asked one morning, trying to drop a hint.

Gretchen didn’t answer.

“Can you check your shoes?” Abby said.This excerpt is a great example of how Grady Hendrix’s writing operates. It’s smooth and clear. Hendrix isn’t out to try and shake up aesthetic outlooks with his prose. He wants to keep you reading. And so the focus is on the build up of tension from each sentence to the next. Pretty classic set-up. First sentence calls the tune, the rest fill in the examples. Same with the second graf. More and more. And even in the second graf, the immediate visceral reaction of bad body odor is compounded by Abby’s trapped feeling. All of these examples/tight summary are punctuated with a small zoomed-in scene that plays with the back and forth of teenagers so well. (I’m refraining from quoting endless yards of hilarious dialogue between teens in this review. Read the book. It’s better in context.)

(125)

Gretchen, then, is possessed by a demon. Abby learns this from the exorcist, Brother Lemon--a member of a power-lifting, God-praising, borderline homoerotic band of brothers. (If you watch Workaholics, think of the guys from the episode “The Lord’s Force.”) Brother Lemon “sees” a demon-shadow over Gretchen’s face during a performance and calls her out. From here on, Abby is on a mission to rescue her best friend from the demon.

What ensues is tension and release. Hendrix builds up hope, then destroys it in the next scene. Why is Gretchen trying to encourage Perfectly Perfect Margaret to quit eating and drink these hard to find diet shakes? Why is Gretchen encouraging Glee to work in chapel with Father Morgan? Why is everyone so goddamned excited to go to a Gross Anatomy Lab? It goes like this: Abby finds something out, then the fact is worthless. This is exactly what works in a horror novel. And I’m here for it. And for the excellent references to TCBY, Ponds face cream, Mickey Mouse telephones, Miami Vice, Dallas, obligatory John Hughes references, leaning hard on the available tech of the day--VHS, answering machines, and so on.

One would expect Hendrix’s horror fiction to be spot on, considering the insane amount of pulpy, bad, hackish, downright opportunistic shlock he’s read in write Paperbacks in Hell or keep updating folks with his monthly newsletter with recs on paperback horror. And it is spot on! Delightfully so. I sound a bit like an old man reviewing his daughter’s novel on Amazon--but seriously, if you want some tense, fun, 80s throwback sparkles in your Trump Era shitstorm, then this the paper vacation is for you.

tl;dr

Yummers: Balances tongue in cheek humor with soul and a true passion for horror. The gross-out scenes are not too long and executed well. I can say that nice animals die here. And people spit up/vomit lots of weird business. But it’s par for the course with demons, ya know?

Bummers: Would’ve loved to have gotten to know Abby’s father a bit more. Also, Abby is shown as an intelligent woman, yet there are some decisions she makes throughout the book that would have us believe that she’s not thoughtful enough to have foreseen the consequences of her actions.